For the first time in the English language, a comprehensive manual of Buddhist meditation known as Anapanasati (the development of mindfulness of breathing) is available.

This kind of Dhamma topic in poetry is for consideration in order to see the truth of that phrase clearly and go on considering till that feeling really happened and then mind has changed by that truth which cause a feeling of pity, carefulness, changing an unworthy habits, washing all annoying feelings out of the mind and got a cleanness, clearness, calmness instead by a proper behavior of each other.

Don Swearer was never ordained at Suan Mokkh, but he is a brilliant scholar of Buddhadasa Bhikkhus life and works. He had even recommended the revered monk to divide his sermons into series, keep an audio recording of each and every one of them, and compile and transform them into book form later. Since Buddhadasa took up Ajarn Don’s suggestion, we now have a sizeable collection of his works—a real treasure.

The tradittonal artist of Siam had little connection with the credo of the modern artist. He did not try to work in an original, individual style. He did not aim at expressing his own personality or his particular philosophy; in fact, he rarely signed his name to the work. Even as an individual he may have been one part of a painting team, perhaps a specialist in painting architecture or figures. The murals seem to have been planned or directed by one person, and the wat records occasionally give a name, but a close inspection of the various scenes will reveal slight differences of line and technique like the differences in handwriting of individuals even if they are copying the same model.

This lecture "Some Marvellous Aspects of Theravada Buddhism" was delivered by Than Achan Buddhadasa in the second session conference of the Sixth Sangayana at Maha-pasanaguha, Rangoon, Burma, on December 6, 1950. The conference was attended by learned people of Theravada Buddhism. The lecture is another very interesting one which shows learnedness of the lecturer, who was so much honored while being so young. Since it is hardly available for people to read, the Vuddhidhamma Fund for Dhamma Study and Practice republishes it once more to preserve the original manuscript and to benefit dhamma-studying people in general.

The content of this book was delivered about thirty years ago in front of a group of university students who joined the monastic life for only a temporary period of time. It was a time when western culture and modem technology and even political ideological concepts were beginning to exert their respective influences on the Thai thinking and way of life, causing some young people to become western-orientated and seemed to pay no heed to the traditional concepts of values from their own culture.

The content of this book was delivered about thirty years ago in front of a group of university students who joined the monastic life for only a temporary period of time. It was a time when western culture and modem technology and even political ideological concepts were beginning to exert their respective influences on the Thai thinking and way of life, causing some young people to become western-orientated and seemed to pay no heed to the traditional concepts of values from their own culture.

This book presents a series of special discourses by Venerable Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu. The discourses were delivered to his student-monks, who were ordained for a limited time. They were somewhat like the last instruction for the monks, before their returning to laity, to take along dhammic concepts and to rightly conduct themselves in the surrounding society. This would bring them peace and harmony with the world. The title of the lecture was Disadhamma, which means the pathway dhamma for mankind.

Dear Buddhist and Dhammic friends who are interested in Dhamma, in the third delivery of my discourse, I will begin with the Third Wish as the topic of my talk. The wish is to lead the world out of materialism. It sounds uninteresting, but in fact it is a matter that deserves the greatest interest. It is materialism that has become our enemy, and it is even more harmful than anything else one could possibly conceive of, especially in this present age when materialism practically reigns over the world.

I will now sit so that you can see what is the correct posture for meditation. (Acariya Buddhadasa then sat in the formal, meditation posture). Today I shall talk about how to practise meditation, or concentration (Samadhi). I shall speak particularly on Mindfulness of Breathing, as requested by the students and some of the teachers. But before I give instructions on how to practise meditation, I would like to mention a few preliminary points. These points will help you to understand the meaning and purpose of concentration or meditation…

What is Buddha-dhamma? Before dealing with the Way to Buddha-dhamma, I would like you to know the meaning of this word. Its meanings are various, but at this time I will confine myself to the meaning which has to do with the highest blissful state of mind.

The subject of today’s talk is “Thanks to those who brought Buddhism to us". Late this evening we have already dwelt on “Dharma-cakra”, the Wheel of Law; its benefits; how it helps allaying sufferings and unravelling problems, and whether it takes us. Our talk was more or less conclusive; the area of elaboration being on advantages to be derived from the practice of Buddhism; how, with Buddhism as our guidance, we can rid ourselves of sufferings and solve life’s problems, and thereby attaining satisfactory state attainable by man.

…What we need to do is create interest in what is known as the heart of Buddhism; that is, working directly toward the elimination of each individual’s defilements. We must work towards extinguishing the suffering of mankind. Once interest has been stimulated people will investigate, consider and seek to understand the essence of Buddhism. Preaching morality for the benefit of society and the state, or interest in Buddhism as a philosophy, or a source of literary enjoyment is less meaningful than self-practice and individual endeavor.

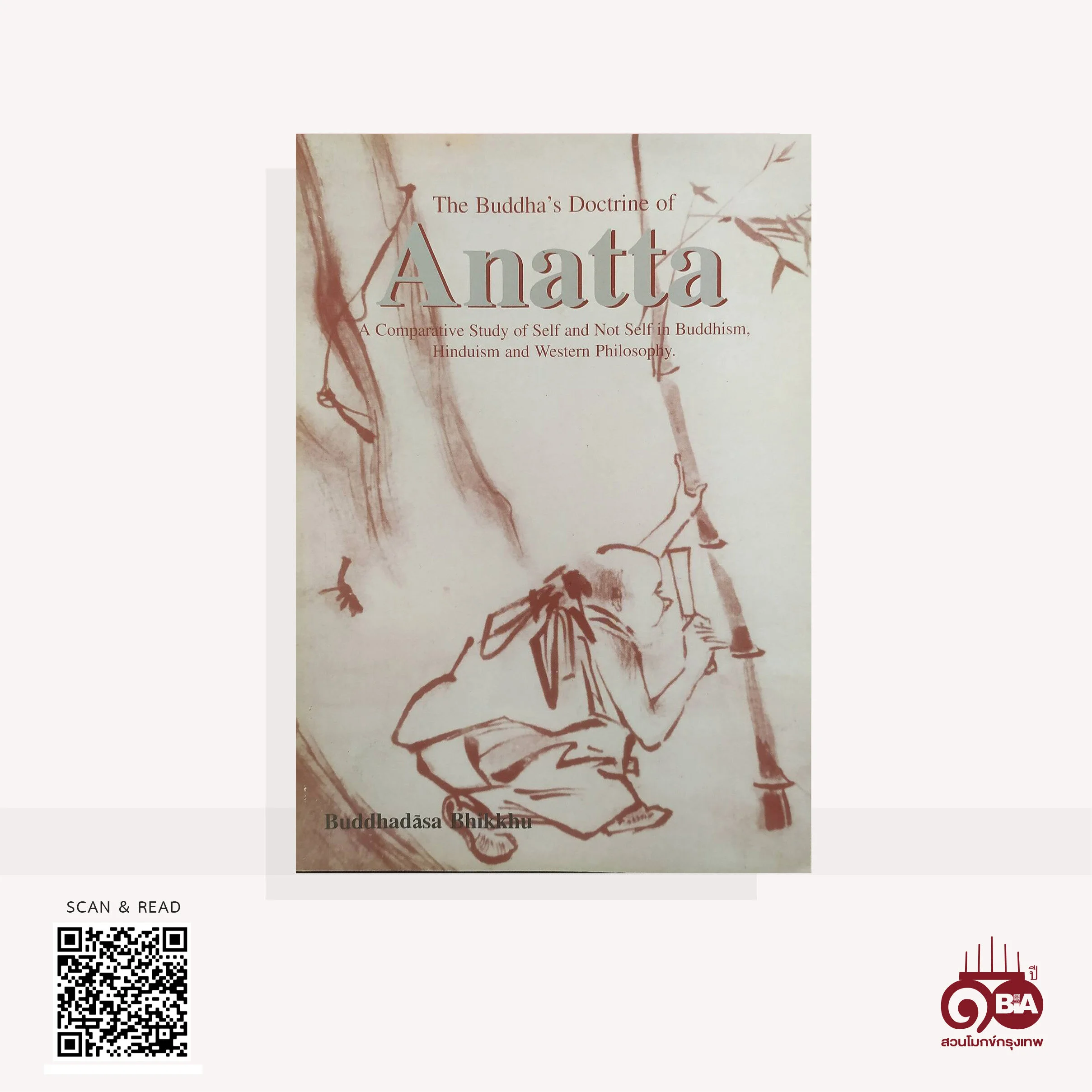

In his letter, the Than Achan also advised: “This book will make people understand better the word ‘anatta’ (not-self) as meant by the Buddha, since there have been too many doctrines which are so ambiguous as to confuse people in general.

In this book, the author draws an analogy between 24 facets of Dhamma and the follow¬ing material entities : a refuge, a torch, a friend, the source of virtue, a medicine, a tree shade, a pool, an island, an umbrella, an abode, a nourishment, a clothing, a weapon, an armor/a fortification, a boat/raft, a pleasant thing, a music/poetry, a sport, an entertainment, a fragrance, a flower garden, a snack, a victory flag, and a mirror.

Ajarn Buddhadasa, when he died in 1993, left behind many notes. Some where in well organized notebooks concerning his Dhamma and scriptural researches. Others were loosely grouped according to the themes and issues that interested him over the years. Many filled up the pages of the diary planners commonly given as New Year’s gifts in Thailand. Most of these eventually turned up in his talks and writings; they amount to preliminary lecture notes. Some were on scraps of paper, envelopes, calendars, whatever was at hand.

This work is a discussion of different kinds of food that is simultaneously intended to be fodder for thought and further contemplation that can lead beyond normal thought. In this text, Buddhadasa Bhikkhu consistently makes a distinction between two kinds of "food" or sustenance—physical and spiritual (or "mental"); through a variety of teachings and examples he discusses what it means to be "hungry" in terms of physical senses and spiritual needs. The overall theme of this work involves showing the difference between the quests for these two different kinds of food and the values associated with and derived from each type of seeking. His similes and metaphors dealing with food are especially clear and useful as teaching devices since they strike so close to home.

To the ordinary person, samsara is generally thought of as something differed and opposed to Nirvana (Pali: Vatta: Nibbana): man is always roaming in this whirlpool of samsara until he reaches out at Nibbana. But I would like to propose here that Nibbana does exist in that very whirlpool. The wise man, searching without external effort, can discover it, but the fool cannot; and it is the matter of one’s own ability. — What is the basis for saying this? —

In this booklet the Ven. Buddhadasa examines the perennial questions "Why was I born? what am I living for? What is the purpose of life?" The answer he gives is that man's task in life is to break free from the bondage of his own mental processes.

Our world nowadays has fallen into the whirlpool of danger, so much so that we inevitably have to solve the problems arising from this situation by the method of ‘exchanging Dhamma while fighting’. But those who are fighting have never realised this truth and they may not even be ready to listen to it. This is the point I have taken here to complain about. When things are like this what should we do? This is the point that I want to present for discussion.

The talk recorded in this booklet deals in particular with the special language which the Buddha, Gotama, used in teaching. The author has called this the Language of Dhamma. But since the Higher Truth or Dhamma is constant, independent of time, place, and teacher, the language in which it is discussed is to a large extent international. The language which the Buddha used in expounding the Dhamma has a lot in common with that which Jesus Christ used in teaching that same Dhamma. So, though this talk was intended specifically for a Buddhist audience, much of it is equally relevant and to the point in the context of Christianity or any other religion.

Our discourse today deals with the subject which you all know, which is : Dhamma — The World Saviour. Now we must realize that we have made the supposition that Dhamma is the world saviour. Therefore, by logic, it must be tenable that the world has to have Dhamma, so that Dhamma may protect or save the world. And what makes it possible for Dhamma to exist in the world ?.

I am pleased to deliver the SINCLAIRE THOMPSON MEMORIAL LECTURES, FIFTH SERIES, for it will help create an atmosphere of mutual understanding among the followers of both Christianity and Buddhism, and also make people understand their respective religions at the same time, for the audience here is both Buddhist and Christian.

The subject we shall discuss today is one which I feel everyone ought to recognize as pressing, namely the following two statements made by the Buddha: “Birth is perpetual suffering.” (Dukkha jati punap-punam) and “True happiness consists in eliminating the false idea of ‘I’.”