The Giving of the Dhamma Eyes

Receive the wisdom, know the truth

Buddhadasa Bhikkhu wanted to make Dhamma study easy, enjoyable and accessible to all people. He further wanted to illustrate that throughout history, drawings, paintings and sculpture were a means by which Dhamma was communicated to ordinary people.

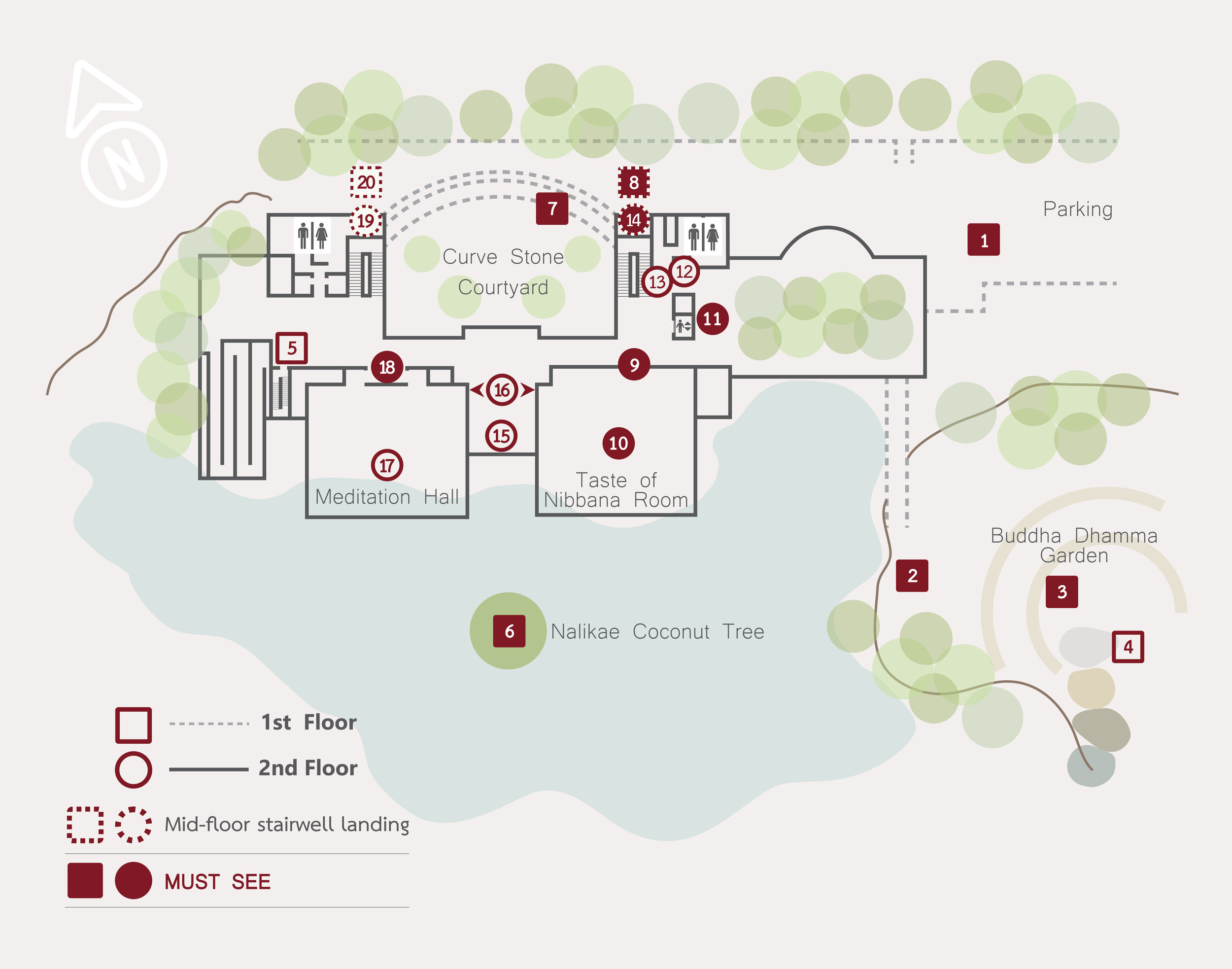

At Suan Mokkh in Chaya, he created what he called a Spiritual Theater. It is a two-story building presenting the Dhamma through visual art, both ancient and contemporary, along with photographs, audio and video.

“Theater of Spiritual Entertainments is necessary for these beings which instinctually need entertainment, which is a spiritual support, a fifth support in addition to the four physical supports (food, shelter, clothing and medicine). Please help to manage them for the use and above-mentioned benefit of everyone.”

Among the Theater’s more prominent pieces, and one Buddhadassa Bhikkhu often used in his teachings, is a large mosaic titled The Giving of the Dhamma Eyes installed on one of the Theater’s exterior walls.

The eyes refers to Dhamma or wisdom, the realization of truth that the Buddha taught. Without an eye, one cannot see the light and the world. Without the wisdom, one can neither realize the truth of the world.

Alas, those eyes he refuses,

Running away blind and headless.

Perhaps I should stop giving eyes.

Such pity for those who desire a closed eye.

But some do wish to wait,

To procrastinate time and again.

If there were a few more who seek light,

The darkness in this world will disappear.

Through restraint, contemplation, and patience,

Take the hands of others and strive,

To give the eyes without despair,

And eventually the world will see light.

Alas, those eyes he refuses,

Running away blind and headless.

Perhaps I should stop giving eyes.

Such pity for those who desire a closed eye.

But some do wish to wait,

To procrastinate time and again.

If there were a few more who seek light,

The darkness in this world will disappear.

Through restraint, contemplation, and patience,

Take the hands of others and strive,

To give the eyes without despair,

And eventually the world will see light.

The great Pharaoh has a stock of eyes through which to offer Dhamma to people. The Pharaoh may represent the Buddha, his disciples, monks or anyone who teaches and spreads Dhamma. The abundance of eyes, coupled with the Pharaoh's hand gesture, illustrates that the Dhamma is everywhere, readily available for one to study and practice.

Despite the Pharaoh’s eagerness to give the eyes, few people come to receive them; many run away blind and headless. This suggests a society more content to pursue sensual pleasures and consumerism than to seek spiritual wisdom.

The headless mass population are unrestrained, represented by their nakedness. They can hardly control themselves in terms of ethics and moral principles—having the tendency to violate them without any shame.

The few people with the eye are neatly dressed, humble and composed. They would be ashamed of wrongdoings, and dare not violate ethical and religious codes of conduct.

This mosaic was conceived and installed by Kovit Khemananda, a young Bhikkhu at Suan Mokkh at the time, who later went on to become one of Thailand’s most revered artists, poets and Dhamma teachers of the 20th century. Kovit recounts that Buddhadasa Bhikkhu was very enthusiastic when first considering the idea, and suggested, “Make it look Egyptian.”